This is an edited excerpt from Maya Sharma’s book, Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India. Through ten intimate, tender narratives, the book paints an emotionally powerful picture of the lives of women, or those assigned female, that love other women, in small town and rural India.

Ishqful thanks to Maya Sharma and Yoda Press for permission to publish this excerpt. Get the book here on Amazon Kindle and the Juggernaut app.

Illustrations by Vidya Gopal

Before I actually met Vimlesh the first time, it was her voice that drew my attention. Somewhere in the middle of introductions at a union workshop on women, gender and work, came a voice surprisingly loud for a woman. ‘Vimlesh Pandit,’ she said, and then jerkily supplied the name of her union and the place she came from. She is shy, I told myself and looked up. She had a crewcut. Her brown eyes were set in a round face with chubby cheeks. In trousers and a full-sleeved shirt she looked like a teenaged boy.

The first conversation that drew us together was about our common love for Rajasthan. I became more alert when she said she was single and free as a bird, and intended to remain so until the end of her days. ‘I have a right to do what I want,’ she said defiantly. And then one day a letter arrived from her. I wrote back at once, she replied, and after some more letters had been exchanged, I asked her if she would allow me to write her story.

—

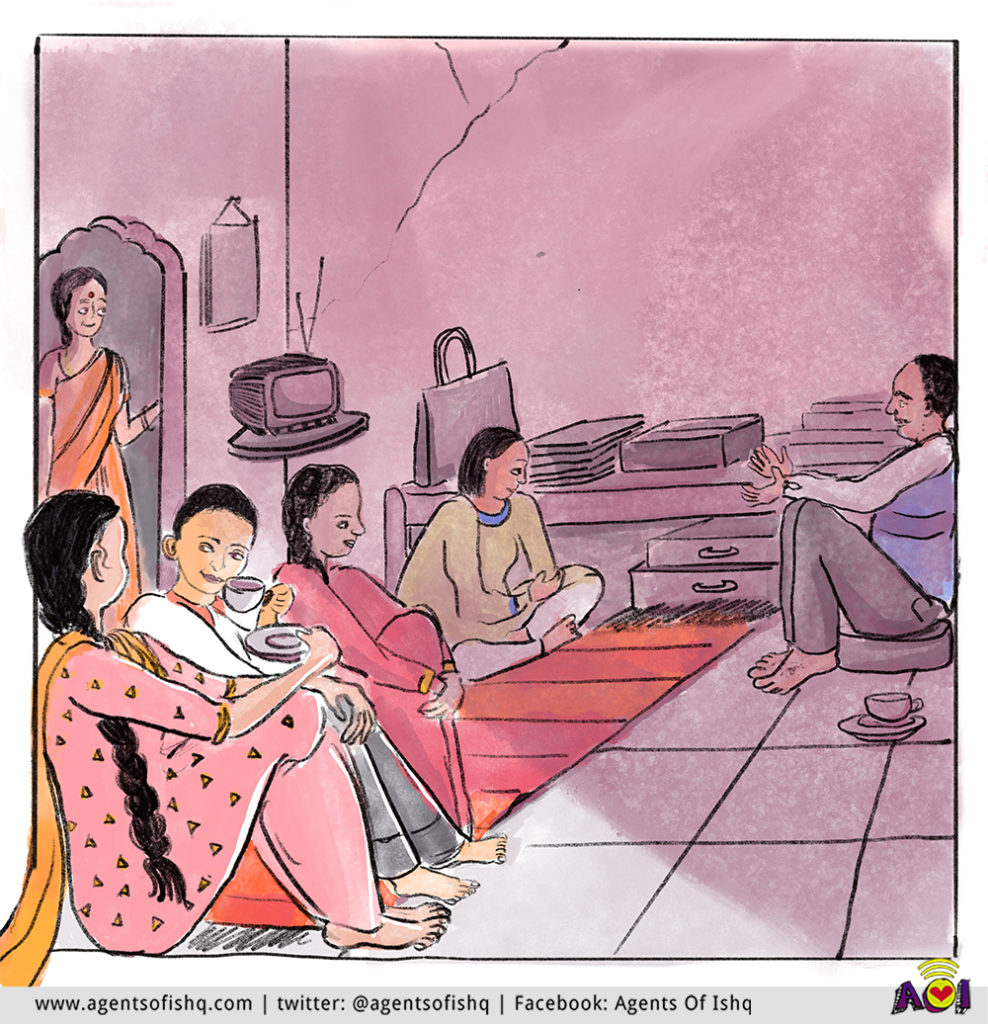

Vimlesh had her own room, in her family home, but her only truly private space was her mind and her body. I observed that even when she sat among us, she some- how kept herself apart. One day, she took us to meet her friend Munka.

Observing her here one could not have guessed that she was reserved by nature. As I praised the old architecture of the house, Vimlesh entered with tea and interrupted my commentary, ‘Munka’s mother will leave the house to her sons, because that is the custom,’ she said in an ironic tone ‘Even if the sons don’t bother about her, and care is provided by only the daughter. Amma, who do you think will protect your daughter and provide for her, after you? Don’t you think about this?’

‘Beta, it is the sons who inherit,’ Amma replied without hesitation.

‘Then Munka will stay in my house, regardless of whether her brothers want to keep her or not,’ Vimlesh said firmly. ‘Everyone needs a place to lay their head.’

The way Vimlesh and Munka talked and laughed, the way they teased one another, put me in a quandary. It was rare to see such an open demonstration of love considered illicit and perverse by social norms. I wondered if Munka was indeed Vimlesh’s special friend. After we left, I said to Vimlesh, ‘In Munka’s house you seemed so different, relaxed, joking….’

‘Yes, I am different with her. She is special. I confide in her. But my life is empty, blank without colours….’

‘What do you mean?’

We had reached the main road. It was somewhat depressing to hear the stoic Vimlesh speak this way. She raised her arm and hailed a three-wheeler, saying, ‘It is time for you to go, when we meet again we will talk some more.’

Suddenly, abruptly, this initiating and terminating of dialogue, the persistent weight of unasked and unanswered questions within which we sensed further questions, a strange flailing about for reassuring certainties—it was difficult to assimilate the load of such emotion. I could not grasp it, and I was unwilling to depart in the midst of such ambivalence. But Vimlesh left me no option. Her demeanour did not indicate that she wanted to share anything further.

As we seated ourselves in the three-wheeler I said, ‘Write to us.’

‘Yes, and you also write.’

We did write to Vimlesh in the following months. In response, she wrote how she was faring, adding, ‘I want to ask you one question. You have learnt so much about me, will you tell me something about yourself, because I have a full right to know.”

I marvelled at Vimlesh’s forthright clarity. What she was really asking for was a greater equality in the relationship. In telling her story and making her family accessible she had made herself vulnerable to us. I wrote back that I would be only too glad to talk about myself.

* * *

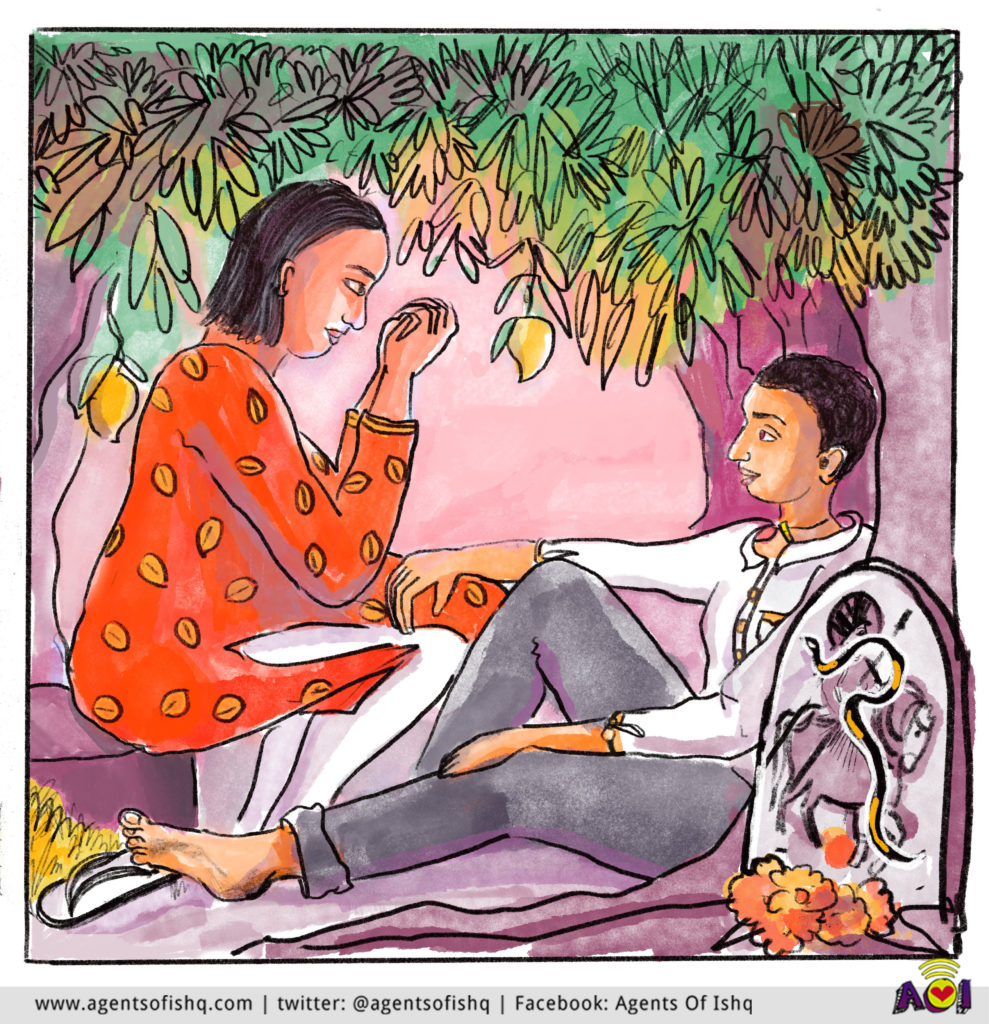

On our next visit, the opportunity to talk to Vimlesh alone presented itself. We left the house, walked along the bank of the pond and entered to a mango orchard. Dense shade and deep silence, a corner of this earth woven by sunlight sifting and flickering through the leaves. We were about to sit down when Vimlesh said, ‘Don’t keep your back to that direction. It has a shrine dedicated to Tejaji Maharaj.’

We turned round. Carved deep into an arched stone slab on one side was a coiled snake with its hood raised and flared. Right across the middle was a proud rider with a regal moustache and a turban tied round his head.

‘Snakes are symbolic of sex and sexual desire, but it is a motif which has come to denote only male-female desire,’ I remarked. ‘And this does not hold true for all people.’

‘Yes, it is not mine,’ my friend said, ‘Neither is it yours.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed, ‘Vimlesh, tell me, what is your truth? Who do you desire, is it Munka?’

A slight gust caressed the mango leaves. As they quivered, Vimlesh said with quiet simplicity, ‘No, there is someone else. She lives in another town. Munka knows about her. All the women in the factory know.’ So easily she said it, without ado. And how long it had taken us to ask!

‘In the factory no one mocks me to my face. I am not bothered by others’ opinions. Everyone has the right to eat what they want, wear what they want, live as they choose. From the beginning, I have dressed in this way, like a man. And I have always preferred women. Why it is so, I have never thought about too deeply. But it is not important to have an answer to everything. You ask if I have heard the word “lesbian”. No, I have not heard it. I consider myself a male. I am attracted to women. Why create categories, such deep differences between male and female? Only our bodies make us different. We are all human beings, aren’t we?’

‘Bodies make us men and women,’ I said.

‘Is that so? Tell me something, do bodies alone make us men and women? First of all, we are not that different when we are young. . . . When my body began to change like all men and women’s bodies do, I felt strange. I did not like it. Besides, no one had prepared me for these changes. I thought, because of these changes I cannot stop living. I had to overcome the shock, adjust to these new developments in my body. If it was within my control, I would change my body just as I have chosen to wear men’s clothes. I say I am a man. I choose to be one. Despite our physical differences, we can be who we want to be and do what we want to do.”

‘I have met several women who are attracted to women, but I understood the full implications of this in depth only after seeing Jyoti at my cousin Baby’s marriage. . . .’

‘Our family went to Aligarh for the ceremony. Crowds of relatives, dholak, music, songs, mehendi, clothes and make-up, food—it was a festive atmosphere. I was standing below the stairs when I saw Jyoti. As soon as my eye fell on her, I recognised something, some deep bond, though I was seeing her for the first time. I stepped forward and said, “Are you looking for Baby? She is upstairs.” Jyoti pushed her way through us and raced up the stairs, declaring loudly, “These city people have no manners!”

‘During that wedding we kept encountering each other. When she was not present, I couldn’t concentrate on anything, when she was around I always felt happy. Baby teased me, saying I had fallen in love. Looking at Jyoti, something was aroused in my soul. We both fell in love. She was in Aligarh, I was in Ajmer…. We wrote letters. A year after Baby’s marriage, she too got married. For a while I kept meeting her.’

‘Her husband did not like it at all….One day we were sitting on the bed, chatting and joking. Suddenly her husband gave her a hard slap. I was enraged, but what could I do? I stopped meeting her, stopped writing. The one I love, why should she suffer on account of me? My love always demands sacrifice. Nothing physical took place between us. We desired one another, that was where it stayed, to sit and talk, holding hands and hugging one another. We felt so close to one another.’

‘To this day, I am pure. Sometimes I think I will take a vow of celibacy or become a renunciate, give up all attachments.’

‘Is that possible?’ ‘What else can I do?’

‘Who is this girl you have mentioned?’

‘Kanak teaches children in a school in Bharatpur. These days she is angry with me. I went to Bharatpur for some work and returned without meeting her. Now she is studying for her MA exams. We can meet her together.’

On the way there Vimlesh walked with her hands in her pocket, her stride confident as she stopped to ask the way to Kanak’s house, ‘It is a rented house, not their own. Kanak’s father now says, “What is the point of owning a house, when my girls go to their husbands’ houses, who will be left here to take care of my property?”…’

‘Do you think Kanak will get married?’

‘Kanak’s father will not agree to any other arrangement. She has turned down many proposals. She says she does not want to marry.’

‘Would your parents, brothers and sisters accept your living with a woman into the house?’

‘To conform to society, they will raise objections. But internally they will accept my choice.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Well! They do understand I am different. But to this day I have not asked Kanak what she wishes. We desire one another but we have not even touched.’

‘Never touched? But one always wants to touch the person one loves, knowing that perhaps they wish the same….Have you ex- pressed your feelings to her?’

‘She knows.’

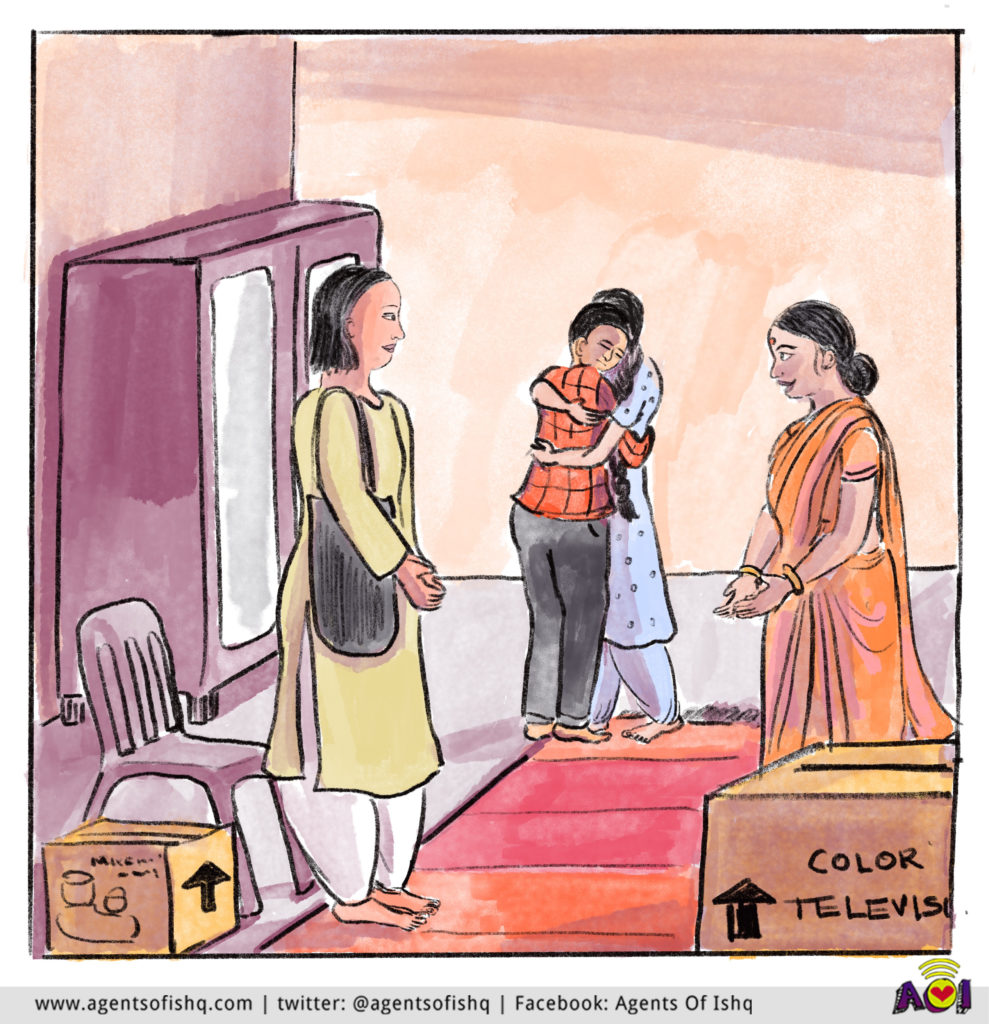

At Kanak’s house, the door was open. Kanak was standing by a tree in the long courtyard. She was tall, slim, fair, dressed in a polyester salwar- kameez, her dupatta neatly folded over her shoulders. She appeared to be the same age as Vimlesh. A long plait swung below her waist, moving in rhythm with her neck as she turned to Vimlesh and clapped her hands with a scream of delight. Vimlesh’s face lit up. Then Kanak exclaimed angrily, ‘I don’t want to talk to you! Why didn’t you visit me the last time you were here?’ She was not in the least disconcerted by my unfamiliar presence.

Kanak went to the kitchen to bring the tea. Seeing there was one cup less on the tray, I asked, ‘Who is not having tea? You, Vimlesh?’ ‘I only want a little tea. We do not need two cups. One cup is sufficient for both of us.’ She took a few sips and slid the cup towards Kanak, who lifted it and took a big sip.

‘Come, let’s go up. Bring your camera, you can take our photos.’ As we climbed the stairs to the terrace, she added, ‘She has my photo but I do not have hers. Take her picture and send it to me.’

On the terrace I squinted at them through the lens while they adjusted themselves into a pose against the parapet, close together, smiling. Vimlesh put her arm around Kanak’s shoulders. Kanak pulled away. Vimlesh glanced at me and said, ‘Did you see that? What were you asking me earlier? Can anyone do anything?’

Kanak quietly slipped her fingers into Vimlesh’s hand and said, ‘Yes, now take our photo.’

Face half-hidden behind the camera as I adjusted the focus, I said, ‘Kanak, how would you describe your relationship with Vimlesh?’ As I pressed the button she replied without hesitation, ‘A love affair. I love her.’ I walked to the far side of the terrace and left them together.

So long as we participate in silencing our own desires we will have to live off stolen moments, brief trysts on terraces, in one another’s eyes, in dreams, between this town and that town, our visions shrinking like the stubby and shapeless noon shadows at our feet.

A few months later Vimlesh came to the city on union work. When we met she seemed happy and more at ease. She wanted to know how I was. After sharing some events of my own life, I asked, ‘How are things with you and Kanak, is there any progress?’

‘Yes, there is some progress. This time when I went to Bharatpur I went to meet her. We kissed and embraced. But we could not say or do more, we were both so embarrassed, it happened so suddenly. It was our first time. I thought my heart would split, I just got up and left. I was trembling. Later we talked on the phone. I cannot understand it. We were eating food at home, she took a barfi, bit off a piece and put it in my mouth. I don’t know how, she actually came to my brother-in-law’s house to see me on her own. When I said, “I am sleeping alone in that room,” she came along with me…. We lay side by side all night, talking. She says, “I have done your share of studying as well! Don’t be tense about the future, you do not need to study.” She says, “I will elope with you.” On February 14 she sent me a Valentine card….’

‘I don’t know where this is going. The next time I am with her I will surely confront her, ask her what she wants, what she is thinking. . . .’

Three months later we got a letter from Vimlesh. Kanak was engaged to be married, she informed us. After she got the news, Vimlesh went to see Kanak, who refused to meet her. Vimlesh tried to phone her but Kanak would not respond. ‘If only she had spoken to me once, I would have understood. She owed it to me, to us, our friendship….’

Just when she had begun to hope! What could I say that would make it better, bearable? I tried to remind her that in all likelihood Kanak had been forced into agreeing to marry. I reminded her that Kanak had resisted the pressure for a long time. I repeated what I had told her earlier, that it was time they frankly discussed their mutual expectations. I suggested to Vimlesh that she write to Kanak. I assured her that we were willing to give whatever support was needed. She wrote to me saying she had written twice to Kanak but had got no response. ‘I want to die, my life is meaningless, no job, no money, nothing. I am angry with you also. You said you would come but you did not, I got the message you had called. I hoped you would call again. I want to talk with you.’

A few days later we met in Bharatpur. I called Kanak at the school where she worked. Vimlesh stood quietly beside me.

Kanak’s voice sounded small and forlorn. ‘Please bring Vimlesh. I have to see her.’

On the way to Kanak’s house Vimlesh said, ‘Please do not insist I eat anything or drink tea there.’ I remembered what Vimlesh had said about being able to eat with only those people with whom she had some understanding. This was her expression of hurt and anger.

Kanak’s family had shifted to a new house—a bigger one with more rooms. When we turned to go in, Kanak came from behind and held Vimlesh in a close hug, completely hiding her face in Vimlesh’s chest. While the rest of us stood pretending normalcy, Kanak simply would not let Vimlesh go. Her mother urged me to move. This was a hug deeper than a meeting of two friends.

I asked myself, why is Kanak marrying? As I walked inside the room I saw a huge carton holding a television set, the first sign of dowry. Kanak’s mother followed my gaze ‘Some things I have bought now, others we will buy later. Sit, please. You have to come for the wedding.’

I thought of Vimlesh, Kanak and innumerable others who stand on shaky ground long, long before their life even begins. Though Kanak longed for Vimlesh, she relinquished her dream in order to maintain family honour. She had won for herself the label of a ‘good’ woman. She had even freed herself of the certain struggle and danger she would have had to negotiate daily had she opted to live with the woman she loved.

Vimlesh walked in slowly a few minutes later. Too casual, I thought as I looked at her. Her face was calm.

‘Where is Kanak?’ ‘She is coming.’ When Kanak’s mother got up to make tea. Vimlesh said, ‘We have to go. We will not have tea.’ ‘Don’t go right away,’ Kanak said as she walked in. She looked thinner and darker. We exchanged greetings and she looked away, blinking back her tears. When the tea was brought in, Vimlesh picked up her cup and put it on the window ledge behind, while making polite remarks. Kanak looked at me in desperate appeal. ‘She will not drink it.’

Raj was telling me about the boy Kanak was marrying. Kanak and Vimlesh got up and went out on the balcony. I could hear them whispering as I sipped tea.

A little later Vimlesh returned to the room. ‘Are we ready to leave?’

‘Yes.’

We said goodbye. Kanak did not come down to see us off. As soon as we were alone, I asked, ‘Well, what did she say?

‘She said that if I had come to her with the proposal before March, that is, before she got engaged, something could have been worked out…. But she also said that women have no choice. “My parents said yes to the boy’s family, if I said no… It cannot work for us if we go against the wishes of our parents.” These are her words.’

Vimlesh shared her sense of anger and betrayal in the letters she wrote to me, vowing that she would break off all contact with Kanak. But when we met several months after Kanak’s marriage, she said Kanak had called. ‘What was I to do? There are so many women but it is her I love. Maybe I should not have talked with her. I am angry with her. But I talked to her. What could I do? She has told her husband about us. She even told him she loves me.

He has asked me to come over. But I do not want to see him, nor hear about him. Before her marriage Kanak was loudly proclaiming our love, and then in the end she withdrew. What can one do? I am telling you, though I do not tell anyone at all, I am missing her.’ Looking away, Vimlesh said in anguish, ‘I wish she were here with me, sitting right beside me. I know there is no point in such thinking, and yet….’

‘I did what I have never done before, I went to the dargah and bowed my head in that Court of the Almighty. I asked Him to give her to me. Before she withdrew from me the whole world seemed so wonderful, and now nothing seems worth living for. Thoughts of her fill my being, and it causes me so much pain.

‘We cannot love anyone just anyone. If only we knew why we love the ones we do, perhaps it would be easier to find someone else to love. Before Kanak there have been several other women but it was not possible to reciprocate….’

“Even now, a month ago, I met a woman. I had gone to my sister’s house in Jodhpur. This woman lives above my sister’s place. She openly told me she loves me. She is married and has one small child. In the night when I went up on the terrace to sleep, she was there. She approached me saying that she had lost her heart to me. I could not think of anything to say to her.’

‘Then it began to drizzle and the raindrops were enough reason for me to get away without really answering her. “You will get wet,”

I told her, as I folded the cot.

* * *

After the rain that day, two summers later, a small patch of blue led up to a full sky. Vimlesh’s window in the shop opened on to a potter’s household and in the wet earth behind the potter’s wheel Vimlesh found an answering echo of her longing in the eyes of the woman who stood beside her father helping him knead and prepare the clay.

I liked the portrayal of the protagonist who accepts being gay as a very natural order of things. The writing is lucid and observant.

The tensions at so many levels makes the reader want to keep reading. Writer captures the details of characters’ desires and the conflicts and tells a captivating story.