Dr (Prof) Rajan Bhonsle is a leading sexologist and urologist in Mumbai, who has been practicing for over 30 years. He is a consulting sexologist, the head of department of sexual medicine at KEM Hospital in Mumbai, and a professor at GS Medical College in Mumbai.

Indian men are obsessed with the size of their penis. You’d think that after spending 30 years as a sexologist, I’d hear less of the two of the most common questions — “Can I increase my penis size?” and “Do I need a long penis to satisfy a woman?” But, no. Even after telling men that they don’t need a long penis to pleasure their partner, they never stop with the size-related questions.

This type of myth-busting is one of the reasons why I became a sexologist. Back in the 90s, when I finished my MBBS, there was no specialisation in sexology. There wasn’t even a subject called ‘sexology’ in medical training. But something that happened to my friend and his wife made me take up the challenge of studying this field.

My newly-married friend and his wife had a nightmarish first night — she ran away from him in the morning, calling him a ‘pervert’. Now, my friend hadn’t done anything out of the ordinary. Since her family completely left out the part about how kids are actually made but taught her everything else about being a ‘good wife’ (cooking, cleaning, taking care of kids) and since she had never had sex before, he’d taken the time to explain it. So her first encounter terrified her. Back then, there was no easy access to the internet or open conversations about sex. So, imagine this — you have no clue about sex and you spend the first night with a man you hardly know. And suddenly you’re told that sex involves stripping naked and letting a man enter your vagina? No wonder she panicked. But her fear received no empathy.

So, I decided to pursue sexology purely to help open our dialogues about sex.

Every time I think about my friend’s case, I think of how much the problem could have been solved with simple counselling. It becomes even more important in what people call ‘weird’ cases.

For example, I had a male patient who suffered from paraphilia, a condition where someone fantasises about atypical objects, behaviours and individuals. This patient was attracted to nothing except a male wig. He would masturbate to the wig he kept at home. It sounds really strange, I know.But when he was 10 to 12 years old, he was very close to his maternal uncle who came to live with him. His working parents found this convenient. His uncle paid him a lot of attention. After winning his confidence, his uncle started masturbating on the child. The only memory of the entire incident he had was that of his uncle’s wig. As he grew older, he came to associate sex with a wig and it became a permanent fixture in his mind. It took me a lot of time to help him disassociate sexuality from a wig. I didn’t do this because it was ‘abnormal’, but because he had feelings of shame associated with it. No matter how strange, it’s okay to have a fetish as long as it doesn’t mentally affect the patient or others in his environment. It would have been dangerous if I’d tried to ‘fix’ him rather than understand how he ended up with his fetish in the first place.

This patient was deeply helped by counselling, but this is not to say medical intervention is any less important. In the last 10 years, there has been tremendous progress with medicine — viagra and other sexual stimulants have changed the game entirely. But for the first 15 years as a sexologist, before the advent of new development in sexual medicine, counselling was the only davai.

But it can be a double-edged sword. In the early days of my career, I used to get very easily invested in a patient’s condition after sessions of counselling. I once had a patient who had been sexually abused by her father and was incapable of forming any sexual relationships. Learning about how deeply she was scarred really took a mental toll on me. It made me angry. And this in turn affected how I did my job. Even coming to me for consultation was a big deal for her because of all the stigma attached to both sexual abuse and sex. She wanted to have a healthy sex life but her traumatic events prevented her from it. Stigma made her feel like it was wrong to even think about sex after you’ve been sexually abused.

And stigma has been my prime nemesis. The most common male sexual problem — premature ejaculation — is influenced by stigma. One of my patients was ashamed to talk about his premature ejaculation problem because he felt he was not a ‘real man’ if he couldn’t satisfy a woman. This type of social conditioning can also result in performance anxiety, like it did with my patient.

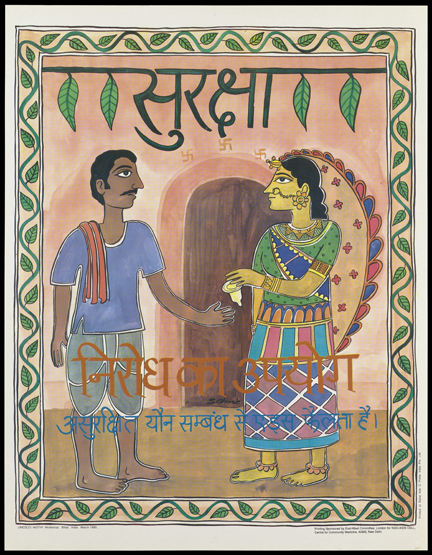

If stigma controls something as simple as premature ejaculation, imagine how it influences patients with sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Sexually active men avoid taking regular tests because they fear they’ll find out if they have an STI. I had a patient who acquired an STI because he refused to get himself tested in spite of rashes on his thighs. Only when things got really painful did he consult me, after being referred by a general physician. After a few tests, we came to know that he’d had gonorrhoea for months without doing anything about it.

We have to be particularly sensitive about cases that involve STIs, because patients amplify its effects too much in their heads. Similar sensitivity has to be displayed while treating transgender patients. Last year, a transgender patient consulted me after she identified herself as a woman and thought that she’d be attracted to other women because she believed ‘transpeople are gay’. This affected her mentally. She is an LGBTQ rights activist and it was surprising how easily she’d believed this false stereotype. I had to explain to her that being transgender and being gay or lesbian are not mutually inclusive. Sexual orientation is how someone is biologically wired, while gender is what they psychologically identify with.

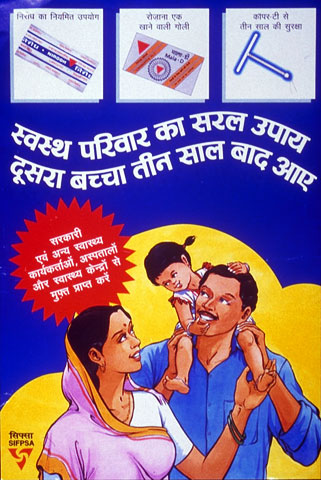

Among all the genders, one thing I’ve noticed is how a woman’s sexual desire is not given the same importance as a man’s. My work in villages in India, particularly on my last visit to villages near Guwahati, have also been very telling about how men perceive sex. I’ve conducted sexual awareness camps in villages across India and one of the primary things I’d notice is how the responsibility of birth is put largely on women. Men would hesitate to come to me for a consultation because they didn’t want to find out that they could be infertile. They’d instead send their wives. The onus of birth being put on women is very common in cities too. The mardaangi problem is very strong.

This leads to a common myth I constantly need to keep busting that only men can consult a sexologist because women have gynaecologists to consult. I do have more male patients than female, but it’s wrong to encourage women to go solely to a gynaecologist. If a heterosexual couple is trying to have a baby and the woman goes to a gynaecologist, she gets prescribed multiple tests without being asked to speak to her partner about his fertility. The first question I ask my female patients in cases of infertility is — “Has your partner undergone a semen test?” A gynaec will prescribe treatments solely on the basis of the woman’s physiological problems in her physical and sexual life, but a lot of problems are things that sexologists can give women a holistic perspective on.

But holistic perspectives don’t end at psychological trouble. They also involve undoing wrongful self-diagnosis. You know, the type who log on to WebMD and think they have some STI or are pregnant and take drastic measures? Yeah, I’ve had several of those patients. With the advent of dating apps like Tinder, sex has not only become more exciting but also urgent. But people rely heavily on the internet for information. The internet is like a knife — it can be a useful tool if used properly. But self-diagnosis, especially for problems related to sex, can be dangerous. And it’s not just youngsters, a lot of my older patients also misdiagnose themselves because they fear the stigma attached to sexual problems; too much to even consult a doctor.

It’s become easier to do this today, but stigma and a culture that has a crisis-based approach to health still prevent sexually active people from consulting sexologists to make informed decisions about their bodies and sexual lives. Many experienced adults still have basic questions about sex. A Mumbai-based couple recently consulted me because they’ve not been able to orgasm in spite of having sex multiple times. Of course, orgasm is not guaranteed through penetrative sex. But it also turned out that they were unaware of how penetrative sex works. The couple did not know the difference between a urethral opening (from where a woman urinates) and the vagina (the opening used during penetrative sex). They thought the vagina is just one large multi-purpose hole. The man was trying to penetrate the urethral opening, which caused the woman a lot of pain and absolutely no pleasure to either of them.

There’s also a general assumption that women orgasm only through penetrative sex or even that women orgasms easily. This is untrue. Like this couple, many patients are puzzled at how having penetrative sex has not led to female orgasms. There’s a general lack of awareness about the different ways in which pleasure can be achieved — the different forms non-penetrative stimulations that can lead to orgasm. (Even here, there’s no guarantee that the woman will reach orgasm. It’s difficult to explain to some men that achieving orgasm is a subjective, continuous effort. It’s not like men can push one button and poof — orgasm!)

People ask me such questions outside of work too, and it becomes difficult to draw the line. I feel the urge to answer but I resist after a while. This is my bread and butter. Is it wrong to think I should get paid to answer deeper questions?

Because deeper conversations can only be had in person. Despite all the exposure to the internet and media, couples, and especially men, don’t engage in basic sex education. Mummy-daddy never sit and tell their sons and daughters about what happens to their bodies during puberty, so teenagers grow up unaware about conversations on sex and sexuality. They only end up relying on their peers (or porn) when they start becoming sexually active, who, like them, are not reliable sources for accurate information.

As a professor, I am constantly engaging with young minds. Young people today are more exposed to information, but information without guidance can lead to confusion and isolation. Especially if what they’re going through emotionally and sexually doesn’t fit into a conventional bracket. So it becomes my job to not just give proper information but also help people clear their own sexual lenses — to look at themselves better.