Illustration by Shikha Sreenivas

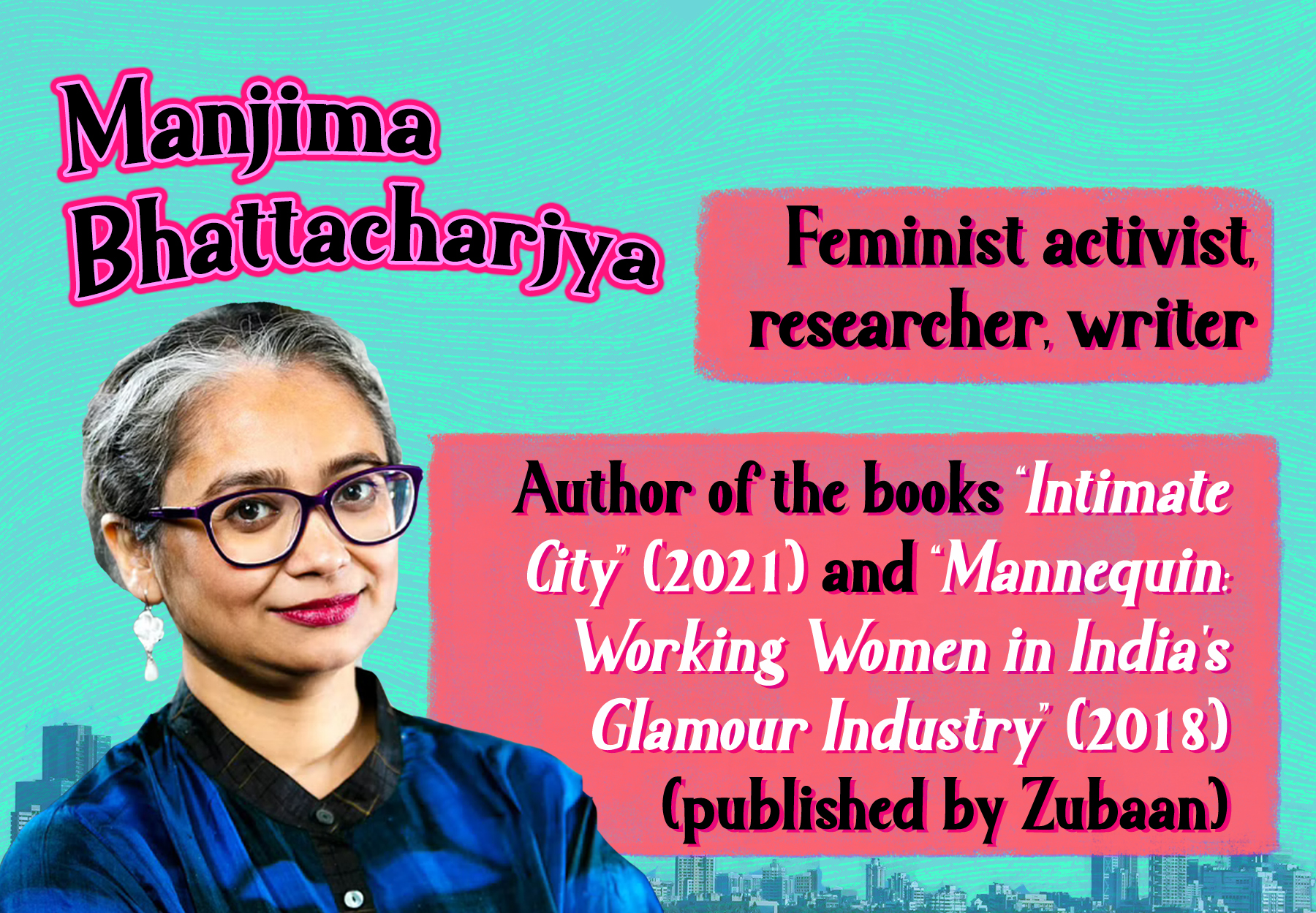

In 2021, Manjima Bhattacharjya – feminist activist, researcher and writer, published her second book Intimate City published by Zubaan Books. The book takes a look at the lives of sex workers in Kamathipura, Mumbai’s famous red-light district. During the book launch, co-hosted by Agents of Ishq and Zubaan, Manjima spoke to Paromita Vohra – founder and creative director of AOI, about her journey with the sex workers’ movement for over two decades and how she came to write this book.

In this edited interview, Manjima discusses the space sex workers claim within the feminist movement, her experience of recording a changing Kamathipura, discovering stories of surprising intimacies in an otherwise stigmatised profession and the shadowy larger domain of sex, the impact of the internet revolution and iron-fisted laws that claim to rescue sex workers.

Manjima, could you begin by taking us through a timeline of the discussion and debates around sex workers within the feminist movement?

Sex work has always been a contentious issue for feminists because, in a way, it touches on the heart of everything that feminists have found very, very sacred like questions of choice, consent, bodily autonomy, and so on. In the West, feminist engagement with sex work started in the 60s and 70s with the second-wave of feminism. There were these ‘sex wars’ which had two positions. One group of feminists felt that prostitution was the poster child of patriarchy. It defined everything that was wrong, and was the ultimate oppression of women. They said if we abolished prostitution, then patriarchy would be gone, dismantled. They were called the abolitionists. The second feminist position which also included sex workers who had a feminist consciousness said prostitution was labour. That women can consent to trade in sex, which the abolitionists refused to believe.

When it came to India and other parts of South Asia, the issue was mostly framed around trafficking, the traffic of human beings for forced labour. When I began working in the women’s movement in 1997, trafficking was being discussed in a big way also because globalisation was happening. There was a lot of migration; women were moving across the world. So, the debates became about migration and women leaving insecure environments to give their labour as nannies, as factory workers, as sex workers – all kinds of labour, in other places around the world in search of better futures. This meant that, you know, even women who had voluntarily consented to work in prostitution for various reasons, who wanted to stay in it, were identified as victims of trafficking waiting to be rescued and removed from that situation.

Also, sex workers were seen as vectors of HIV-AIDS. And the focus was always on poor women in red-light areas. Even men who were having sex with men, male sex workers, trans sex workers and so on were identified as vectors [of the disease]. The work around HIV-AIDS led to the massive mobilizing of sex workers and from then on, we’ve had a very strong sex workers movement in India that is premised on the sex work as labour ideology. This is very powerful in its own way because of the numbers it has gathered over the years. It has been the main platform for the sex work as labour ideology. But the bigger block has been the anti-trafficking lobby which continues to operate as a rescue team. These two groups are in opposition to one another and often work against each other.

In the 2000s, there was an important dimension added to the sex work debate when it was reframed as a caste question. Dalit feminists said that prostitution needed to be abolished not for moral reasons, but because historically most women in prostitution have been Dalit women. Historically, it is caste-based prostitution that has played a big role in South Asia, India in particular. For them it [sex work] was similar to manual scavenging or undignified labour, which had to be reclaimed in order to attain dignity, or Manuski – the Ambedkarite term.

There were also positions on livelihood which bar dancing or the bar dancers debate brought up. So, there are all these different kinds of positions which exist at the moment. There are other smaller positions that exist as well, you know, where people are trying to find their way to really initiate some dialogue and conversation beyond the larger fixed ideas around sex work.

One of the amazing things about feminist movements is the personal journeys we make. When we enter feminist spaces or the feminist movement when we are young, we take on other people’s fully formed ideas about feminism. Then, as we encounter completely divergent views, we are confused and ask questions of ourselves and then slowly arrive at newer understandings. What was that journey like for you within your work?

If I look back at the last 20 years, I remember initially going to Amsterdam [as part of my training] and feeling very uncomfortable in red-light areas seeing women (sex workers) standing inside these rooms with glass walls. I must’ve been in my 20s then. Another time when I was in Khandala at a training with a group of sex workers, there was a pleasure and pain exercise we did. We had to map our bodies and mark points of pleasure and pain [in the body].

When that exercise happened, I realized that I had gone in assuming that the sex workers will know a lot about sex, their bodies, or that they have some autonomy over their bodies, but it wasn’t so. There were so many identities they had besides being sex workers as poor women, dalit women, single women, single mothers. I mean, that was a very defining moment for me.

There are more such moments when you actually meet sex workers and talk to them. Like, you can’t call it false consciousness (the idea that you have been forced to believe some untruth as true about yourself) if someone says that I want to stay in this occupation of sex work or that I’m here comfortably now. It’s possible their entry into the profession was violent, but they don’t want to be rescued now.

So, my position, I think, over the years has shifted more to the site of the sex workers’ movement. Amidst all this, I also feel that there are so many limitations to the conceptualization of sex work itself. Because at the moment, it seems to have a very broad definition. It [sex work] can give self-confidence, make you feel empowered to a certain extent but the everyday stigma, the discrimination, all of it stays. And you can’t keep proving that I love my work every single day. Nobody loves what they do every single day, right? You have good days, you have bad days. Somehow it feels like there is a burden on sex workers to keep asserting that they are workers, without really critiquing that they do work in bad conditions, have bad relationships, have bad situations that need to be addressed. That violence exists. So, these frameworks do fall short ultimately.

In your book Intimate City, you’ve described Kamathipura very beautifully and passionately. Could you tell us about how Sudharak Olwe’s photographs of the place informed your book?

(Sudharak Olwe is an award-winning, Mumbai-based documentary photographer.)

One of the methods that I used in looking at Kamathipura is looking at its cultural history and things like photographs, archives and so on. Sudharak has this massive archive that he has been making through the years. The first picture of his that I saw was of Sunil Dutt’s hands filled with rakhis. Apparently, Sunil Dutt used to come to Kamathipura every Raksha Bandhan and all the women there used to tie him rakhis. It’s an incredible picture – his hand with rakhis and all the women’s hands around him! I spent a day at Sudharak’s archives and he and his family gave me lunch and it was a really amazing insight into the place. I kept telling him that you must figure out how to actually archive these in a certain way. Maybe he has. But yeah, his narrative was about a changing Kamathipura. He felt and he realized that Kamathipura is changing very, very quickly, and so it was him speaking as well through his photos, that I also interpreted in my own way. Besides him, Kamathipura has also been mapped by NGOs quite a lot because they need to know where to stock condoms, provide health services etc.

In your description of Kamathipura, you present to us a place that has not just disease and difficulty, but also beauty and joy along with the pain. You mentioned that Kamathipura has changed over the years, how has it changed and why? Where does it stand today?

The change is multi-dimensional. Bishakha Dutta, a filmmaker and the founder of the organisation Point of View has worked a lot in Kamathipura. She said what has changed there are AIDS, raids and trades. It’s really a great phrase!

Kamathipura is very prime real estate. And it’s a thing in Bombay where redevelopment keeps happening, right? When this began happening in Kamathipura, the prices went up. Also because of AIDS and other political shifts, like the shift of the wholesale markets to areas like Vashi and Turbhe, the footfall dropped. The everyday working-class labourers who would come to Kamathipura stopped coming there. Plus, the mobile phones were emerging so women didn’t really need to be in Kamathipura to have customers.

If we look at raids, they constantly happen in the area and make it difficult to live there. The police claim it is to rescue trafficked women, especially trafficked minors. In 2012, the year that I studied that area, of the nearly 500 people who were rescued, only 7 were minors (according to official statistics from the Mumbai Police). And then in 2000, 300 women were rescued apparently but only two were minor. Yet the raids continued. I mean, when I was doing my study, Bishakha and I went to see the Simplex Building in October, in which 400 people were removed overnight in a raid that lasted 3 days. It became too much for people to continue living there.

With trade, when people moved, since Kamathipura is a place that is always chaalu – running 24/7 – it became ideal for small industries to operate from there. The area has its own system where everything is provided for. It’s an ecosystem of its own. All of this has led to the decline of the red-light area. In many other places, red-light areas are preserved because they have cultural heritage, some sort of history involved. But not Kamathipura. The statistics say that in the 80s, there were about 100,000 women in prostitution there. And now there are about 1000 commercial sex-workers there.

The location of Kamathipura is also interesting in the sense that it lies contiguous to the Cinema Hall area. Madhushree Dutta’s film 7 Islands and a Metro (2006) talks about how historically, the cinema halls, the performance spaces and the redlight districts were all in continuation with each other like in many parts of the world. Because there is a moment in world history when there is global trade so ports emerge and people go in and out of them and the pleasure district is one – sexual pleasures, performance pleasure, cinema pleasure, everything is present alongside.

I mean, slowly everything gets gentrified, right? Professions get gentrified, spaces get segregated and then eventually the gentrification of the entire neighbourhood happens, which happened in Kamathipura too. But I guess the really interesting question is the human need for pleasure, a double meaning attitude of one thing having many meanings and the shadowy existence of all the people who occupied places. Colonialism had many courtesans move to Bombay and many of them got into the film industry or into Parsi theatre. Similarly, sex work also entered a completely different space – the internet.

And I think it’s important to remind people that the early internet was not the Internet as we know it today. It was like a pleasure district in the sense that it wasn’t a place of work like today. It wasn’t completely under corporate control. There was no social media as such. Except for a few people who accessed email, the Internet was a place to browse, chat, where you’re anonymous, where you’re endlessly pursuing some kind of fun or pleasure, and sometimes an urgent desire or other.

So, what happened with the coming of the Internet? What did you find in your study?

If we look at this idea of gentrification, the pleasure district also went through it. Like theatre for the masses or even classical singing found a different kind of audience. But sex-work remained non-gentrified. Today, you go on the Internet to find pleasure but the internet is also being gentrified is what I’d say. I did an analysis of 105 websites that offer escort services in Bombay and through their images and text and all that, they reveal the ideal escort and the ideal client that they imagine. Both client and escort are classed. They are also upper caste. The names that they choose for the escorts are usually upper caste girls’ names, you can tell by the surnames. They are very Bollywood-like, very filmy. Like Natasha Oberoi. Or it will be a girl-next-door kind of name – Smriti Mishra or something. And the client they have constructed is a discerning gentleman with fine taste. He is classy, he is global. So, gentrification in that sense.

But there is also a resistance to this through online chat rooms and notice board kinds of websites where younger boys and so on go because they feel that they will never be the client for the escort. So, they create these networks and groups and clubs and meet there.

Like a rebranding…

Exactly. So, a red-light area becomes an entertainment district or a pleasure district. Prostitution itself becomes sex work and then sexual entertainment like lap dancing or strip clubs. The sex worker then becomes what the American sociologist Elizabeth Bernstein called the “girlfriend experience”. She becomes an entrepreneur who is providing the sex work experience. So, this rebranding is happening at different levels.

Who is buying sex, the kinds of sexual services and even the idea of what is the service that is being bought and sold is also changing. The service is also of intimacy. Which is why although I started off by studying geographies of sex workers, I ended up with a book called Intimate City.

Could you tell us more about this idea of intimacy? What kind of relations have you encountered?

Actually, I found that there are so many men who are cruising the internet and offering services. They call themselves male service providers, not sex workers. And those transactions are not only always for cash, they are for kind too. They are for holidays where someone will pay for you to go on a holiday with them. Like little luxuries, even friendship.

There was an interview that I did with a third party who would arrange for escorts for visiting NRIs and foreigners. But he wouldn’t take money from them. He said, “All I get from them is friendship and a network. Every 15 days some NRIs come and I go around with them because I don’t know anybody else in Bombay. This is my circle, my community.” There are different kinds of transactions happening which don’t fit in the definition of sex work as we know it. Sometimes people are performing multiple roles. Sometimes they are buying, sometimes they are selling, sometimes they are in-between. So, who is the buyer and who is the seller? And the internet and the economy within which all this is happening, I think, makes it possible. For example, in India, there is a certain class of people who work in Uber or Zomato or Swiggy. But in the West, an uber driver can also be an uber client or you know, a Zomato worker can be a Zomato client.

Such a setup really makes us think about this [sex work] economy on the internet in a different way and that’s why, one of the suggestions that I am make in the book is that escorts are maybe not sex workers. Maybe they are gig-workers because they don’t fall into the definition of the informal sector of sex-workers that we know. But they do fall into the definitions we know of gig-workers.

When you say gig-work, it seems that being a sex worker isn’t anymore a permanent or even comprehensive identity and that the class of people within the profession is changing. Also, you mentioned a rise in the number of male ‘service providers’. Could you tell us about these shifts?

Another significant thing to note is there are many women clients because their purchasing power has increased. A lot of the men spoke about these clients, their motivations and so on, with very poignant personal stories. These were women in their 30s, 40s, unmarried, having well-paying jobs and fantasies too. One of the most poignant stories that I heard from a service provider was how he was so surprised that all his client wanted was to go for a trip together, which she paid for, and perform this suhagraat – the first night after getting married. So, she wore a sari, he wore a kurta pyjama, he put flowers on the bed, and it was one of those things that makes you think that what we desire is also so socialised in us.

Nalini Jamila’s autobiography (The Autobiography of A Sex Worker) talks about how even a caress can be and is part of sex workers’ work. In that sense, while the Dalit feminist position exists, it’s also true that a lot of sex workers identify with the private work that wives do. When we talk about domestic labour as unpaid work, we don’t talk so much about the sexual labour of the housewife or what is considered conjugal rights.

Another male service provider also made a note of the moral framework. It’s changing everywhere, he said. He said that one of his uncles was part of some scam and got sent to jail. But his cousin said yes, my father was in jail for 3 months, so what? We have 3 crores now.

So, it seems like the old moral framework doesn’t matter anymore.

(Based on an audience member Meena Seshu’s question) There is a debate around whether sex workers are workers or service-providers. Do you have any thoughts on this?

I don’t know what the distinction of calling sex work as a service offers to us or the sex workers. Does it suggest that we look at the broader economy? Or that the gig or informal economy needs to have some structural change?

Although I do feel that the current idea of the worker is still very vague. Would it be more helpful to understand their rights in terms of the rights of a citizen? How do we get to that point, where beyond worker rights, we talk about safe cities or safe internet because these are concerns of sex work too. So, I think an expansion beyond the current worker definition is needed so these other aspects of their profession, their lives don’t get left out.

The recent anti-trafficking bill (2021) is in the spotlight. What do you think are its implications on sex workers?

So, escorts benefit from propagating the myth that nobody will raid the five-star hotel because it works for them. But we saw that with ACP Dhoble [Mumbai Police], they were raiding bars, massage parlours, anything. So, it wasn’t just brothels or just poor women in red light areas who were being rescued.

With the 2021 anti-trafficking bill, they have brought in the National Investigation Agency, the NIA, as an implementing partner. Now, the NIA is sort of an anti-terrorism agency so the criminalisation [for trafficking] has increased. Raid rescues are going to be the machinery to implement the law. In this proposed law, they are also trying to bring the digital realm into surveillance which means right now, post-covid, sex workers who are working through sexting and using apps that receive money, etc. are all trackable. The law is introducing mandatory reporting. So even journalists cannot report about women sex-workers without the obligation to report it to the authorities. Health workers will be forced to report. So, this law has completely conflated trafficking with sex work.

The implication will, of course, be huge for sex-workers but for all people generally. Like, for example, if I am in a relationship and I send a sexy picture to my partner and the same day we go out for a date and you know, on Paytm she sends me money, the evidence can connect the two and the definitions in the law are very vague.

Such a law is a control over women’s sexuality. The vision that women need to be within the institution of marriage, within the family and caste lines was always there in the legal architecture but now this vision has just become tighter and besides, even if you or other organisations support sex workers’ groups, the danger is that they might categorise you as a trafficker. So, anyone and everyone is implicated.

The stories in your book compel us to think differently about what should change about consent, about agency, about violation, and all of those things. Tell us a little bit more about this idea of deliberate choice that you mention in the book and how it helps to think about all the differing debates in a much more compassionate and forward-looking way.

This idea of deliberate choice is actually from Lorelai Lee, a former escort, and is very powerful because it really makes us think about and reflect on why we do what we do. Have we consented to these long hours of work? Have we consented to backaches and working so hard to make a living? I mean, what are the deliberate choices we might make, right? Even having a child is not necessarily a deliberate choice that is available to women. I find it a really important concept that also opens a window into the personal fear within the collective social, public life.

There is your private life in the household which is also actually a social life (because society determines your role at home) and then there is an internal life that you have. I think in that internal life you keep reflecting about the choices you make and the relations that you have with others and that’s the space that really gives us the opportunity to be more empathetic about what we call hypocrisy. It’s an in-between space, a space of influence, which can embrace some ambivalence. That is the place where people can change. It’s like a scaffolding, you know. I realised this when a male service provider said that he had never thought that he would find such nice people in what he was doing. That was one of his biggest takeaways from being in that space. He was a Blackberry-wielding corporate guy, actually. But he was able to open himself up to that realisation. I feel although it really doesn’t break any existing ideas, it surely opens up conversation and shifts things around.